If you watched the Drama #Towalkinvisible last night on BBC about the Brontës it may have struck you how little attention was given to the pseudonyms adopted by the sisters, other than an invisible hand dramatically writing the names in ink: Currer Bell, Ellis Bell, Acton Bell. That lack of detail is down to the fact that little is documented as to where the names came from. This presented my inner Hercule Poirot with a superb challenge. The following is the result of my research into the possible origins of the Bells. My favourite speculation is the French connection!

Why Bell?

Was the name Bell randomly chosen without any great thought?

This idea is not persuasive; there was nothing random about the Brontë family: trips a few miles down the road were planned with the precision of an Antarctic expedition, evidenced in the many letters that would to and fro between Ellen Nussey and Charlotte before either ventured forth to visit the other. Bearing this in mind it is likely that considerable attention was afforded to such an important aspect of their potential published personas. The relative solitude of their existence lends intensity to their lives where even the most menial activity is given heightened significance. For all her inadequacies as discussed earlier I find myself agreeing with Gaskell when she suggested:

…Life in an isolated village, or a lonely country-house, presents many little occurrences which sink into the mind of childhood, there to be brooded over…Thus, children leading a secluded life are often thoughtful…the impressions made upon them by the world without…the accidental meetings with strange faces and figures — (rare occurrences in those out-of-the-way places) — are sometimes magnified by them into things so deeply significant…[1]

With this in mind it must have been very exciting for the sisters to enter into this particular masquerade and consequently we must ponder the very real notion that considerable thought went into the choosing of pseudonyms. However, due to a dearth of primary sources revealing sources of inspiration for the names little has been said about Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell in an academic medium. The only clue Charlotte gives regarding the origin of the names Currer Bell, Ellis Bell and Acton Bell, the names eventually adopted, is that they must sound Christian and male. Because no other documentation exists, the origin is somewhat of a mystery and can only be intelligently speculated on.

Much of the speculation regarding the surname Bell points to the arrival of the new curate in Haworth, Arthur Bell Nicholls. This theory was the preferred choice of Winifred Gérin in her biography where the following is proffered:

…The name Bell may have been chosen by the arrival that summer of their father’s new curate, Arthur Bell Nicholls.[2]

I suspect that this idea has been tagged on because of Charlotte’s marriage to Nicholls in June 1854. Nicholls had arrived in Haworth first in May 1845[3]and up to the point where the pseudonyms were chosen there is nothing in Charlotte’s correspondence to suggest that she harbours any feelings for him strong enough to inspire an imaginary surname. The opposite, in fact, is the case, as the following extracts from letters to Ellen Nussey reveal:

…Who gravely asked you “whether Miss Brontë was not to be married to her papa’s Curate”?

I scarcely need say that never was rumour more unfounded-it puzzles me to think how it could possibly have originated-A cold, far-away sort of civility are the only terms on which I have ever been with Mr Nicholls-I could by no means think of mentioning such a rumour to him even as a joke-it would make me the laughing- stock of himself and his fellow curates for half a year to come-they regard me as an old maid, and I regard them, one and all, as highly uninteresting, narrow and unattractive specimens of the “coarser sex”…[4]

10th July 1846.

…Mr Nicholls is returned just the same-I cannot for the life of me see those interesting germs of goodness in him you discovered, his narrowness of mind always strikes me chiefly-I fear he is indebted to your imagination for his hidden treasures.[5]

15th October 1847.

Admittedly Charlotte was not in the habit of bearing her soul to Ellen but there was nothing to be gained by coyness regarding the Reverend Bell, consequently it is fair to conclude that the sentiments expressed above represent an accurate assessment of Charlotte’s opinion of the man and therefore deem him an unlikely source for the origin of the literary Bells.

My reading of the Brontës inclines me to make two further suggestions as to who or what the original Bell was. In June 1847, following the abysmal failure of Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell, the publication of which they had paid for themselves, the girls decided to send some well known authors a copy of the Poems. Among the recipients were such literary greats as Alfred Lord Tennyson, William Wordsworth, Hartley Coleridge and the lesser known John Gibson Lockhart. The latter was the son-in-law of Sir Walter Scott and his biographer but had won the hearts of the Brontës as a result of his many contributions to Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine. A letter to Lockhart from the novelist Harrison Ainsworth of November 15th, 1848, held in the Brontë parsonage Museum in Haworth, concerning itself with rumours regarding the identity of the Bells, concludes:

…Currer bell, I agree with you is not a belle; and there must be more than one hand at work to ring all these changes…[6]

I wondered having read that extract was it possible that Charlotte’s wry humour was at work here and Bell was a deliberate choice after the French word belle (denoting female), and in as obvious a fashion as this the Brontë sisters were duping the predominantly male world of literary reviewers.

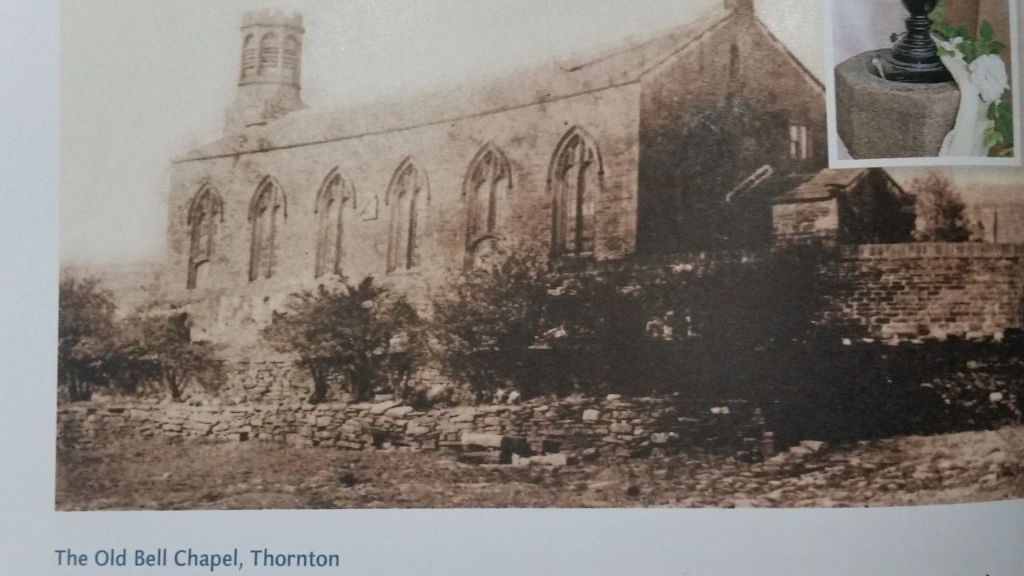

If not a pun on the French word, there is one other possible origin of the Bell surname and would be very much in keeping with the girls’ desire to keep things Christian. Charlotte and her siblings were not born in Haworth but in Thornton and according to Clement Shorter the chapel where the Revd Brontë officiated and where all the children, except Maria were baptised was called Bell Chapel:

…Eighty years have passed over Thornton since that village had the honour of becoming the birthplace of Charlotte Brontë. The visitor of to-day will find the Bell Chapel, in which Mr. Brontë officiated, a mere ruin, and the font in which his children were baptised ruthlessly exposed to the winds of heaven…[8]

Working on a metaphorical level, it is apt that a literary baptism, eager to maintain a sense of the Christian naming should endeavour to incorporate both; even if this was not the case it is a far worthier notion than that suggested by Gérin. Despite the fact that Charlotte would one day be Charlotte Bell Nicholls, in 1846 there is little evidence of her desire to attach herself in any way to Arthur Bell Nicholls, her father’s curate.

Charlotte’s chosen Christian name was, according to Gérin ‘…the least difficult of the three to trace to a recognizable origin…’:[9] when Charlotte was governess at Stonegrappe for the Sidgwicks one of their more illustrious neighbours was a Miss Frances Mary Richardson Currer, of Eshton Hall, Skipton. Miss Currer’s reputation was based on the fact that she owned ‘…one of the most considerable libraries in the north…‘.[10]

Charlotte would no doubt have been aware of the woman and possibly even read books from her collection as Currer was known to make donations to the Mechanics’ Institute Library of Keighley,[11] from where the Brontës borrowed. As Rebecca Fraser has shown in her biography, Mr Brontë joined the Keighley Mechanical Institute shortly after it was founded in 1825 in order to borrow books and provide a wide range of reading material for his children. In their book, Everyman’s Companion to the Brontës,[12] Barbara and Gareth Lloyd Evans give April 8th 1833 as the exact date on which Patrick joined the Institute. [13]

Miss Currer, a wealthy lady, also had associations with the Clergy Daughters School, the possible inspiration for Lowood in Jane Eyre, where presumably, due to a harsh regime, Charlotte’s two sisters Maria and Elizabeth contracted pulmonary tuberculosis and subsequently died. As Gérin has shown, “She was one of the founder patrons of the Clergy Daughters’ School, so that her name must have been doubly familiar to Charlotte.”[14]

One final, slightly bizarre, connection between Charlotte and Miss Currer is the fact that both were already living under an assumed name, as Miss Currer’s father, also a Revd Henry Richardson, rector of Thornton only ‘assumed’ the surname and arms of Currer.[15] ‘Brontë’ was also an assumed name, adopted by Charlotte’s father, Revd Patrick Brontë in place of his birth name Prunty.

The sources for Anne and Emily’s pseudonyms, Acton and Ellis, are even more difficult to identify than Charlotte’s Currer. Realistically any associations made are merely aspirational on behalf of the particular mythology the researcher wishes to promote.

In her biography on Emily, Gérin suggests,’… The poetess Eliza Acton (1777-1859), who had considerable success in her day and was patronised by royalty, may have suggested Anne’s pseudonym to her…’[19] Gérin’s implication that Acton’s success was attributable to her poetry is misleading. Acton did write poetry but without attaining much commercial success or notoriety and had it not been for the success of a further endeavour the literary world would most probably not have remembered the poetess who wrote the following:

I LOVE thee, as I love the calm

Of sweet, star-lighted hours!

I love thee, as I love the balm

Of early jes’mine flow’rs.

I love thee, as I love the last

Rich smile of fading day,

Which lingereth, like the look we cast,

On rapture pass’d away…[20]

The successful venture referred to above was a cookbook. Acton is more remembered as an early Mrs Beeton, of cookbook writing fame. Apparently worried by the lack of popular acclaim, Miss Acton approached her publisher, Mr Longman, asking him to suggest a subject for a book that would be popular. He, according to anecdotal evidence, suggested …a really good cookbook…, and after years of planning and research Eliza produced, in 1845, Modern Cookery for Private Families.[21]

In her article The Brontë Pseudonyms: A Woman’s Image-The Writer and her Public, Marianne Thormahlen observes that ‘…The combination of poetry and domesticity in the person and work of Eliza Acton increases the probability of her surname having been chosen as a “veil” by one of the Brontë sisters. Household chores made up a very considerable portion of their daily lives…’[22] Published just a year before the Brontës’ volume of poetry in 1845 it is highly likely that the sisters were aware of the book and appreciated a commercial success story embedded in domesticity as their lives had thus far been. Gaskell captures this ‘Angel in the house’[23] view of Emily in the following extract from A Life:

…and after Tabby grew old and infirm, it was Emily who made all the bread for the family; and any one passing by the kitchen-door, might have seen her studying German out of an open book, propped up before her, as she kneaded the dough…[24]

If we accept that Charlotte’s Christian pseudonym is based on a real surname it is likely that Anne and Emily’s follow this pattern: the level of achievement attained by the real Acton and Currer was certainly enough to merit admiration and adaptation of their identity and yet their names, not being among the shining lights of the Victorian world, were not household names and thus allowed the Brontës to appropriate them without fear of their own achievements being attributed to others.

Emily’s pseudonym is the most open to speculation. Gérin has nothing to offer:’…There appears to be no clue to the origin of Emily’s choice of name, Ellis…[25] Thormahlen argues, rather convincingly, that the writer Mrs Sarah Stickney Ellis was Emily’s source. If one accepts the above speculations on Currer and Acton it is easy to accept that Emily also based her adapted Christian name on a real surname of a relatively successful Victorian woman.

Stickney Ellis (1812-1872) a seemingly typical middle class English woman, wrote reflectively in defence of the social order of Victorian England and the domestic and social duties of women in that society. Also a conservative novelist, Ellis, addressing the ladies of England in her many conduct books, advised against any activity that would interfere with their womanly duties, activities, ironically enough, such as writing.

Elaine Showalter, in A Literature of Their Own, writes of Ellis in the following fashion:

…If we turn to the books of Sarah Stickney Ellis…The Women of England, The Wives of England, The Mothers of England, and so on, we might get the impression that a wife’s duties were so detailed and overwhelmingly as to preclude any other activity…[26]

Thormahlen argues that while the conservative nature of Ellis may not have appealed to the very individualistic Emily Brontë, her sentiments on governesses in The Mothers of England, must have endeared her to the sisters. Ellis writes:

‘…And here I must beg to call the attention of the mothers of England to one particular class of women, whose rights and whose sufferings ought to occupy, more than they do, the attention of benevolent Christians. I allude to governesses, and I believe that in this class, taken as a whole, is to be found more refinement of mind, and consequently more susceptibility of feeling, than in any other…[27]

As we cannot be sure if the Brontë sisters ever read anything by Mrs Ellis or indeed Eliza Acton, and perhaps they were unaware of the extensive library belonging to Miss Frances Mary Richardson Currer; therefore all of the preceding rationale is highly speculative.

It is empowering from a female perspective to suggest that the choices the Brontës made were calculated to hoodwink the predominantly male literary world as not only were these masculine names belonging to the fairer sex, they could also have been inspired by women of strong character and achievement.

However at the risk of unravelling my own thesis it is equally feasible that the names presented themselves in a serendipitous manner, perhaps some reference in a magazine lying about the Parsonage was all the invitation and inspiration needed to merit their usage.

[1] Elizabeth Gaskell, The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857; London: Penguin Books, 1997), p. 70.

[2] Winifred Gérin, Charlotte Brontë, The Evolution of Genius, (London: Oxford University Press, 1967), p. 309.

[3] Smith, The Letters, Vol. 1, p. 393.

[4] This is part of a letter written to Ellen Nussey, dated July 10th 1846 and reproduced in Smith, The Letters, Vol. 1, p. 483.

[5] Extracted from a letter to Ellen Nussey, dated October 1847 and reproduced in Smith, The Letters, Vol. I, p. 551.

[6] Smith, The Letters, Vol I, p. 530.

[7] Ibid, p. 516.

[8] Clement K. Shorter, Charlotte Brontë and her Circle (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1896), p. 56.

[9] Winifred Gérin, Charlotte Brontë, The Evolution of Genius, (London: Oxford University Press, 1967), p. 309.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Barbara and Gareth Lloyd Evans, Everyman’s Companion to the Brontës, (London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd, 1982), p. 14.

[13] Although not detailed in the book I presume this information is available by accessing the records of the Mechanics Institute in Keighley, particularly when such a precise date can be given.

[14] Gérin, Emily Brontë, pp.185-6.

[15] http:/www.maxiuiliangenealogy.co.uk/burke/royal%20descents/francismaryrichardsoncurrer.htm.

[16] This was contained in a letter written to Emily dated July 1839 and reproduced in Smith, The Letters, Vol. 1, p. 195.

[17] Written to Ellen Nussey on the 26th of July 1839 and again reproduced in Smith, The Letters, Vol. 1, p. 196.

[18] Fannie Ratchford with the collaboration of William Clyde DeVane, Legends of Angria, compiled from the early writings of Charlotte Brontë (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1933), p. 316.

[19] Gérin, Emily Brontë, pp.185-186.

[20] The first two verses of what is perhaps Acton’s most remembered romantic poem first published in a volume entitled Poems by Eliza Acton (Ipswich: R. Deck, 1826) and reproduced on the following web page, http://digital.lib.ucdavis.edu/projects/bwrp/Works/ActoEPoems.htm.

[21] G.M. Young (ed), Early Victorian Britain, 1830-1865, Volume One (London: Oxford University Press, 1934), pp.125-126.

[22] http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/bronte/cbronte/thormahlen/thormahlen.html.

[23] A phrase that denotes a Victorian Sentimentality towards women and based on the long poem by the American poet Coventry Patmore, first published in 1854.

[24] Gaskell, Life, p. 105.

[25] Gérin, Biography of Emily Brontë, p.186.

[26] Elaine Showalter, A Literature of their Own, from Charlotte Brontë to Doris Lessing (London: Virago Press, 1999), p 65.

[27] Reproduced from The Mothers of England, p 353, in Marianne Thormahlen, ‘The Brontë Pseudoynm’, English Studies, 3 (1994) p. 252.

Leave a comment